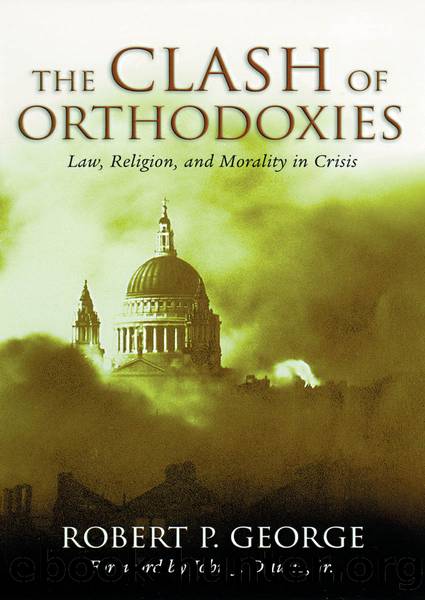

Clash of Orthodoxies by Robert P. George

Author:Robert P. George

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781497651432

Publisher: Intercollegiate Studies Institute (ORD)

Robert P. George

I AM GRATEFUL to Joseph Koterski and James Fleming for their comments on my paper. Father Koterski and I agree more than we disagree. Things are the other way with Professor Fleming, so I will devote this response to his comments (though I will not address every point on which we disagree).

The terms ânatural lawâ and âlegal positivismâ have no stable meaning in contemporary legal, political, and philosophical discourse. It is therefore incumbent upon scholars who participate in discussions in which these terms are employed to attend carefully to the different meanings assigned to them by different writers or by a given writer in different contexts. The price of carelessness in this regard is error and confusion.

Unfortunately, Flemingâs comment on my paper demonstrates my point. Fleming imagines that there is a striking âanomalyâ in my âembrac[ing]â Hugo Blackâs âharangueâ against natural law. âI can certainly understand,â Fleming avers, âwhy a positivist like Robert Bork would revel in Blackâs trashing of natural law. I never thought, however, I would see the day when an able defender of natural law [that would be me] would embrace Blackâs dissent [in Griswold v. Connecticut].â âNotwithstanding George,â he goes on, âone might expect most natural lawyers to defend the dignity and honor of natural law against Blackâs critique [of it].â

Anyone who pauses, however, to consider what Hugo Black was rejecting when he condemned âthe natural law due process philosophyâ of judging (or what Robert Bork is affirming when he accepts the label âlegal positivistâ) will see that Fleming is deeply mistaken. The anomaly he thinks he finds in my analysis is an illusion generated by his failure to observe that the ânatural law due process philosophyâ that Black rejects has no necessary connection to the ânatural lawâ I affirm. Indeed, no proposition central to Blackâs criticism of the opinion for the Court in Griswold contradicts any proposition I hold or have asserted in defending natural law.

In Natural Law and Natural Rightsâthe 1980 book that revived interest in natural law theory among contemporary legal philosophers in the analytic traditionâJohn Finnis elaborated an argument to show that â[t]here are human goods that can be secured only through the institutions of human law, and requirements of practical reasonableness that only those institutions can satisfy.â101 It is this proposition that I join Finnis and a number of other contemporary natural law theorists in defending against moral skeptics and relativists, as well as those particular âlegal positivists,â such as Hans Kelsen,102 who make the rejection of the objectivity of human goods and moral requirements integral to their jurisprudential theories.

Plainly Robert Bork is not a legal positivist of the Kelsenian stripe. His âpositivismâ is expressly restricted to the claim that under our Constitution courts are entitled to enforce only the positive law of the Constitution and are obligated to defer to legislative judgments where the positive law does not forbid legislative action.103 It is simply a mistake to imagine him ârevelingâ in a âtrashingâ (to use Flemingâs deeply pejorative term) of the ânatural lawâ that Finnis and I defend.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19105)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12197)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8921)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6894)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6285)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5808)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5769)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5513)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5454)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5225)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5157)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5091)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4967)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4932)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4797)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4756)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4724)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4517)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4493)